Cressida Cowper, the character fans loved to hate across three seasons of Bridgerton, was revealed in Season 3 to be far more than a simple villain. Her journey from a cutting debutante to a desperate woman facing a grim future peeled back the layers of her mean-girl facade, exposing a character shaped by a loveless home, patriarchal pressure, and a fight for survival that viewers could finally understand.

The Mask of a Mean Girl

For her first two seasons on the ton, Cressida Cowper was the undisputed queen of nasty work. From spilling a drink on Penelope Featherington to flirt with Colin, to making snide remarks about Daphne Bridgerton, her actions were calculated to elevate her own status by putting others down. She was the epitome of the Regency-era mean girl, complete with dramatic fashion and an expression that suggested a constant, wicked internal monologue. Her primary goal was clear: secure a wealthy and desirable husband to secure her position in society. This mission put her in direct competition with other young women, particularly Penelope, whom she saw as an easy target.

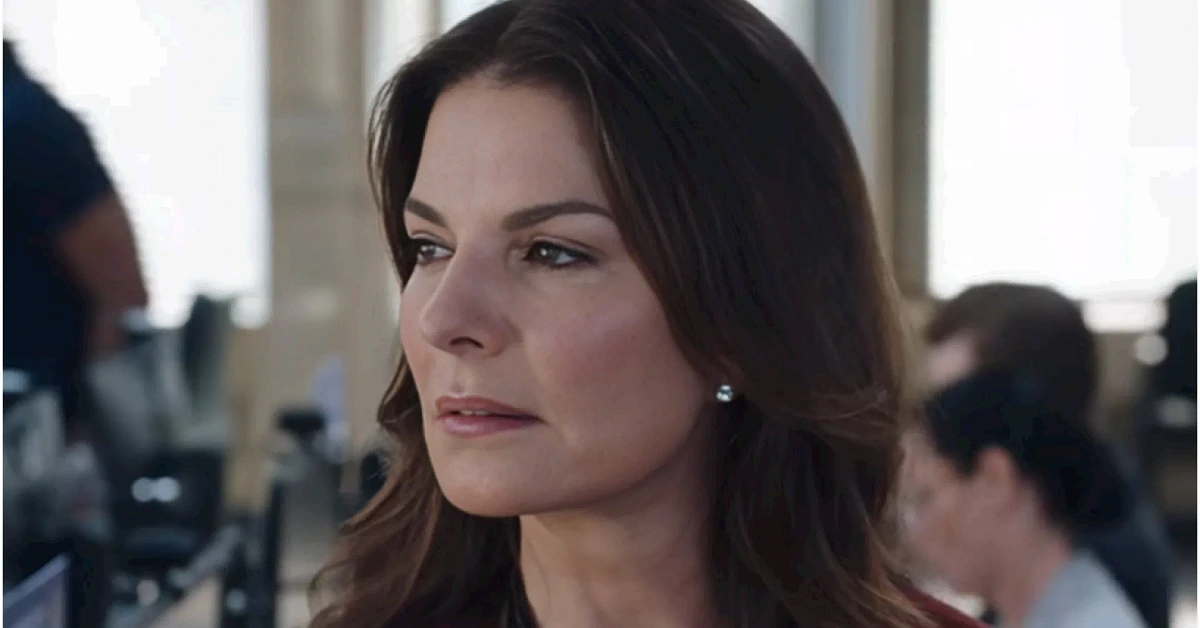

This persona was a performance, a mask she wore to navigate the brutal marriage mart. As actress Jessica Madsen explained, Cressida was “a product of her environment,” a young woman hardened by her circumstances who used cruelty as a form of armor. The performance was so convincing that Madsen received direct messages from viewers saying, “Thank you for letting me hate you so much”.

The Chilling Cowper Household

Season 3 provided the crucial context for Cressida’s behavior by introducing her home life. The Cowper household was not one of warmth or affection. Her parents, particularly her father, were depicted as “ice cold,” offering Cressida no love, understanding, or open communication. Her mother’s advice was famously cynical: “Don’t trust anybody, especially women”. This shattered Cressida’s hope for genuine female friendship and taught her that the world, especially the world of women, was a battlefield.

The stakes of the marriage game were made terrifyingly real for Cressida in Season 3. Under increased financial pressure, her father decided to marry her off to Lord Greer, a man three times her age who despised music, art, and society balls. Faced with a future of somber clothing, limited social engagement, and being a vessel for children, Cressida was understandably horrified. This was not a path to a comfortable life; it was a sentencing to a gilded cage. Her desperation to escape this fate became the driving force for all her subsequent actions.

An Unlikely Friendship and a Glimmer of Change

A significant shift occurred during the summer between seasons, when Cressida formed an unexpected friendship with Eloise Bridgerton. While Eloise was reeling from her rift with Penelope, Cressida was the only one who showed her kindness. This friendship offered Cressida her first glimpse of a different world. With Eloise, who came from a loving family and held progressive ideals, Cressida could momentarily let her guard down.

The impact was visible. In a moment of rare vulnerability, Cressida admitted to Eloise, “It has been difficult to find a husband. It has been more difficult to find a friend”. She acknowledged her own unkind behavior, recognizing that the social season inherently pitted women against each other. When Eloise shared a potentially scandalous secret about Colin helping Penelope, Cressida, for once, chose not to gossip—a small but significant act of loyalty. This arc showed a capacity for growth and a desire for connection that complicated her villainous image.

A Desperate Gambit for Freedom

When Cressida learned the queen was offering a 5,000-pound reward for unmasking Lady Whistledown, she saw a lifeline. The reward promised freedom: financial independence that would liberate her from the obligation to marry Lord Greer or any man. Her decision to falsely claim she was the infamous gossip columnist was not born of pure malice, but of a frantic, last-ditch effort to save herself.

As Jessica Madsen analyzed, Cressida’s choices were “innocent” and “hopeful” in her mind. She didn’t fully grasp the repercussions of stealing the queen’s quarry or the complexity of maintaining the lie. When her plan began to crumble, she resorted to blackmailing Penelope, the real Lady Whistledown. Madsen noted this was a reversion to her only known method of self-protection, a tragic return to old ways when she saw no other path forward.

Also Read:

Conclusion and Lasting Sympathy

Cressida’s story in Season 3 does not end with empowerment or a happy escape. After her scheme implodes, she is publicly disgraced and sent away to live with a relative, effectively exiled from society. For many viewers, this conclusion felt unnecessarily harsh, a betrayal of the character’s development throughout the season. Rather than being rewarded for her desperation or granted a fresh start, she was punished, her fate mirroring the very powerlessness she fought against.

This ending, however, cemented the argument that Cressida is more victim than villain. Her story is a stark illustration of the limited options for women in her world. Without a supportive family, wealth of her own, or a husband, she had no agency. Every action—the early cruelty, the desperate lie—was a strategy for survival in a system designed to crush her. She was not competing for fun; she was fighting for her life as she knew it.

Jessica Madsen masterfully portrayed this complexity, allowing audiences to see the “human side” and the “something beneath” the mean girl. Cressida Cowper remains a flawed character who made harmful choices, but Season 3 reframed her as a tragic figure. Her greatest crime was not her sharp tongue or her schemes, but her relentless, if misguided, fight for freedom in a society that offered women like her none.

Also Read: Taxi Driver 3 Episode 13 Recap: Lee Je Hoon Meets the Crime Architect Kim Sung Kyu