George R. R. Martin wanted his Westeros to feel real. It was meant to echo the brutal history of the Crusades or the Wars of the Roses as much as it drew from classic fantasy. This philosophy extends to his most magical creations: the dragons. In a detailed blog post from July 2024, Martin explained the strict biological rules he follows, inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien’s own approach, to make these mythical beasts feel like believable animals.

The Tolkien Rule: Why Dragons Should Make Sense

The core idea Martin champions is that fantasy is not a license to ignore logic. Even in a world with magic, the creatures need to be physically plausible. He points to a scientific principle that Tolkien respected: no six-limbed vertebrates exist in nature. Animals that fly—birds, bats, pterodactyls—use modified forelimbs as wings; they don’t have four legs and a separate pair of wings.

This is the rule Martin adopted for A Song of Ice and Fire. His dragons are not four-legged creatures. They have two legs and two wings. Martin was very clear on this point, stating, “They have two legs (not four, never four) and two wings. LARGE wings”. He criticized fantasy designs with tiny wings that could never lift a massive body off the ground, insisting his creations obey the basic laws of aerodynamics and anatomy.

“In A SONG OF ICE & FIRE, I set out to blend the wonder of epic fantasy with the grittiness of the best historical fiction. I wanted Westeros to feel real… I wanted my dragons to be as real and believable as such a creature could ever be”.

A Heraldic Mix-Up: When the TV Shows Got the Sigil Wrong

Martin’s commitment to this anatomical rule caused a public, though good-natured, frustration with the HBO adaptations. He explained that in his world, the Targaryen sigil on banners and shields should always show a two-legged dragon, because that’s what real dragons look like in Westeros.

However, he noted that both Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon made a consistent error. While early seasons of Game of Thrones used the correct two-legged design, later episodes and the prequel series changed the sigil to a four-legged dragon. Martin said this was likely because someone looked at a medieval heraldry book, where four-legged beasts are called dragons and two-legged ones are called wyverns, and applied that distinction to a world where real dragons exist. “That sound you heard was me screaming, ‘no, no, no,’” Martin wrote about the decision in House of the Dragon.

More Than Just Legs: How Martin’s Dragons Live and Behave

Following biological logic goes far beyond limb count for Martin. He designed every aspect of his dragons to feel like living predators, not just magical symbols.

- They Do Not Talk: Unlike Tolkien’s intelligent, talking dragon Smaug, Martin’s dragons are beasts. They are relatively smart and have distinct personalities, but they do not speak.

- They Bond, But Are Not Tamed: Dragons can form deep bonds with specific riders, reflecting their personalities, but they can never be fully tamed. They remain dangerous and wild at their core.

- They Have Practical Needs: They need to eat, drink, and breathe. Martin points out they can drown if held underwater and cannot sleep for decades like some legendary dragons because “fire needs oxygen”.

- No Love for Gold: They are not interested in hoarding treasure. “They do not care a whit about gold or gems, no more than a tiger would,” Martin wrote.

- They Are Not Nomadic: Dragons are territorial and tend to stay close to their lairs, like the Dragonmont on Dragonstone. They do not roam freely across continents, which explains why they didn’t overrun the world even at the height of Valyria’s power.

A Different Kind of Dragon: Martin’s Inspiration and Preferences

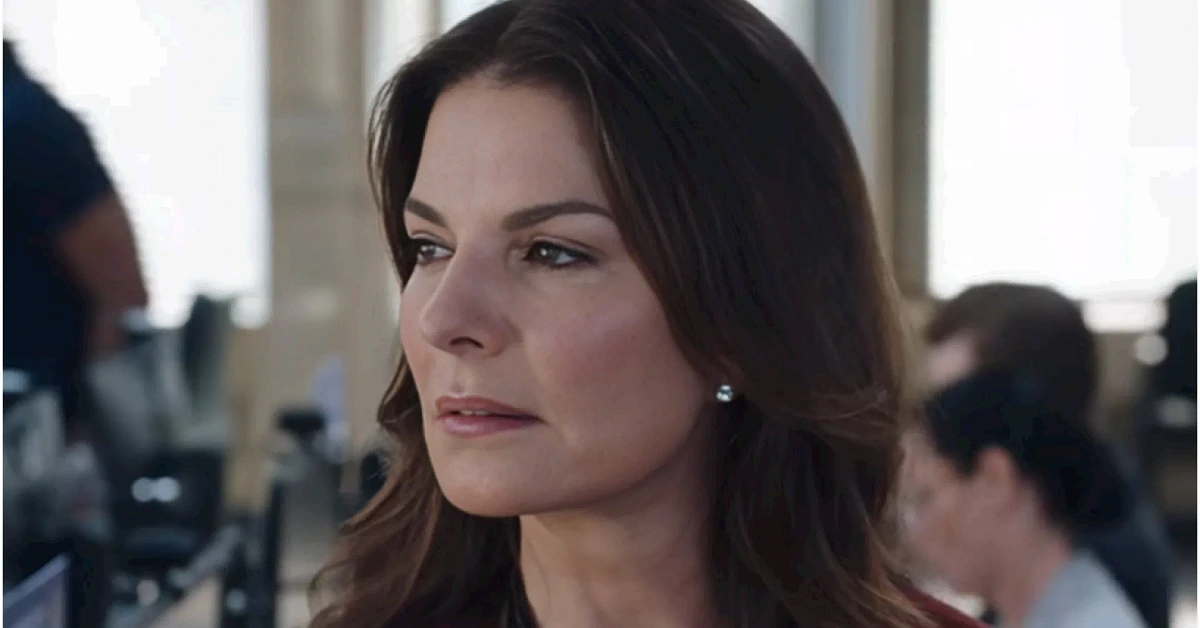

Martin’s blog post also highlighted his favorite cinematic dragons, revealing his taste for more animalistic designs. He praised the dragon Vermithrax from the 1981 film Dragonslayer, calling it an “inspiration for all dragonlovers”. Vermithrax is a two-legged, fire-breathing creature that does not talk, aligning closely with Martin’s own vision.

In contrast, he was critical of the friendly, four-legged, talking dragon voiced by Sean Connery in Dragonheart, calling it a “much inferior dragon in a much inferior film”.

This preference for grounded design is shared by other modern creators. The 2002 film Reign of Fire was noted for trying to create “realistic” dragons that were more like animalistic predators than wise, magical beings, a design choice that has influenced many Hollywood dragons since.

Also Read:

The Author and the Adaptation: Creative Tensions on Screen

Martin’s passion for internal logic isn’t limited to dragon anatomy. He has also been openly critical when HBO adaptations change the narrative structure of his stories for practical production reasons. In a now-deleted blog post, he expressed disagreement with House of the Dragon showrunner Ryan Condal over the removal of a young character, Prince Maelor, from a major storyline. Martin argued the character’s absence lessened the emotional impact and cruelty of the “Blood and Cheese” plot.

While he praised the show’s dragon battles as some of the best ever put on screen, these instances show his meticulous focus on maintaining the rules and consequences that make his fantasy world feel authentic. For George R.R. Martin, whether designing a creature or plotting a dynasty’s fall, the goal is the same: to ground the fantastic in a reality that audiences can believe.

Also Read: Members Only: Palm Beach Cast Pre-Launch Party Recap, Streaming Details and More